Chicago/Turabian Style Guide

Published May 7, 2012. Updated June 21, 2022.

Need Chicago or Turabian style for a paper you are writing? This guide has everything you need to know about Chicago style according to the latest standards.

This page follows the 17th edition of The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) and the 9th edition of the Turabian guide (A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations), though this guide is not officially connected with either.

Here’s a run-through of everything this page includes:

- Here’s what you’ll find on this page:

- What is Chicago style? What is Turabian?

- Paper Formatting Guidelines

- Citing Your Sources

- Notes and Bibliography Style

- Author-Date Style

- Formatting Your Bibliography or Reference List

- Other Chicago Guides

Here’s what you’ll find on this page:

- Introduction to the Chicago and Turabian styles

- Paper formatting guidelines

- When and what you need to cite when writing a paper

- Notes and bibliography style

- Author-date style

- Bibliography and reference list formatting tips

What is Chicago style? What is Turabian?

You may have heard the terms “Chicago” and “Turabian” used interchangeably and wondered what the difference is. Simply put, they are just about the same.

Turabian is a simpler version of Chicago style meant for students who are writing materials that will not be published. Since the CMOS is meant for material that is intended for publication, it’s often used by scholars, publishers, and other professional academics. The Turabian guide is shorter and includes information on formatting rules, the basics of researching and writing academic papers, and citation style. Despite these differences, these two books work in tandem; both are considered to be official Chicago style.

Paper Formatting Guidelines

Since Chicago style is typically used for manuscripts that will be published, The Chicago Manual of Style does not offer many guidelines for paper formatting. This is because publishers each have their own house styles and authors must follow these exactly. There are a few areas where guidance is offered.

- Manuscripts: Generally, manuscripts should be double-spaced (CMOS 2.8). Exceptions are block quotations, table titles, and lists in appendixes, which should be single-spaced, and certain front matter (e.g., table of contents), footnotes or endnotes, and bibliographies and reference lists, which should be single-spaced internally but have a blank line between each separate item (Turabian A.1.3).

- Spaces at the end of sentences and after colons: Chicago recommends one space (CMOS 2.9; Turabian A.1.3).

- Margins: Margins should be at least one inch on all four sides (CMOS 2.10). Certain forms of writing like dissertations or theses may require a larger margin on the left side to allow room for binding, but each institution will have different requirements (Turabian A.1.1).

- Justification: Text should be justified to the left (CMOS 2.10).

- Font: Turabian recommends using a font that is both readable and readily available to most people such as Times New Roman or Arial. Times New Roman font size should be no smaller than 12-point and Arial no smaller than 10-point. Footnotes and endnotes may require different sizing and you should refer to your instructor’s guidelines (Turabian A.1.2).

- Pagination: Pagination of the body of the paper and back matter should use arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.). Front matter like the title page and table of contents should use lowercase roman numerals (i, ii, iii, etc.). For the placement of page numbers, the general rule is to adhere to local guidelines and be consistent. (Turabian A.1.4)

For more specific formatting guidelines, you can take a look at the appendix “Paper Format and Submission” in the Turabian manual.

Citing Your Sources

Chicago style has two citation styles to let readers know that you used information from somewhere else and to show them where to find it.

- notes and bibliography style

- author-date style.

Though different, each style allows you to tell your readers how you found your information. If you’re wondering how these two styles differ from parenthetical citations, this guide on footnotes, end notes, and parentheticals contains more details on each method.

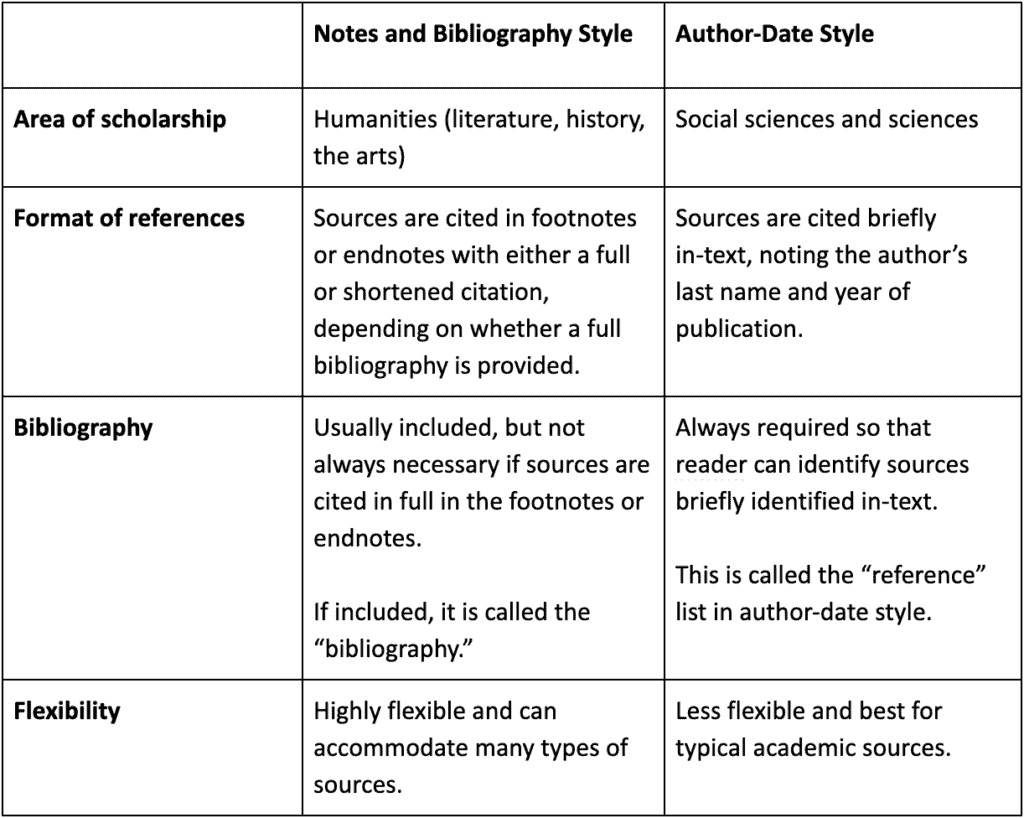

The 2 styles

The first style is the notes and bibliography style. This style uses footnotes or endnotes to point readers to the original source of the information. This style also often provides a bibliography at the end that readers consult, but this is not always necessary if sources are cited in full in your text.

The second style is called author-date style. This style uses parenthetical in-text citation to let readers know to look at the reference list at the end to find the full citation for the information you have used.

Here’s a chart to compare these two citation styles:

You must cite your source in any of the following situations:

- If you quote a source exactly

- If you reword ideas from a source

- If you use any material (e.g., statistics, data, methodology) from a source you read while writing

When citing your sources, you usually need a few key pieces of information:

- Who created the source? This might be an author, editor, translator, or corporate body.

- How can you identify the source? This information will likely include a title, page numbers, volume or issue numbers, and edition.

- What is the publication information? This might include the name of the publishing company, the year of publication, and the name of the journal or book the information is in.

- Where can others find the source? This is important for online sources and singular material like that found in rare book collections or archives. For online material, you’ll want to record a URL or database name if possible. For rare book or archival material, you’ll need the name of the place you found it and the collection name.

Why citing your sources is important

Telling your readers where you found your information is a very important part of the writing process. It gives credit to the hard work others have done. It also lets readers know that your information is reliable—they don’t just have to take it from you; they can go see what other researchers have written about the topic.

Citing your sources also helps readers to understand the context of your project. You can show that you understand the work that has already been done and where your own research fits in.

Finally, your readers might want to build on your research. Citing helps them to know where you found your information when readers do their own research. They might even cite you if you formally published your work. You can read more about how to integrate the research of others into your paper in Chapter 7 of the Turabian manual or Chapter 13 in the CMOS.

Notes and Bibliography Style

This style uses superscript numbers at the ends of sentences. These numbers alert readers that the sentence contains information from another source. Each superscript number refers to a note.

The notes are located at the bottom of the page (footnotes) or at the end of the paper, chapter, or book (endnotes).

- Footnotes make it very easy for readers to find your source, but they can interrupt the document flow.

- Endnotes tend to reduce distraction on the page, but then the reader must flip pages to find the source you cite.

Unless your instructor has told you otherwise, the choice between footnotes and endnotes is up to you. You just need to be consistent and stick to one style or the other.

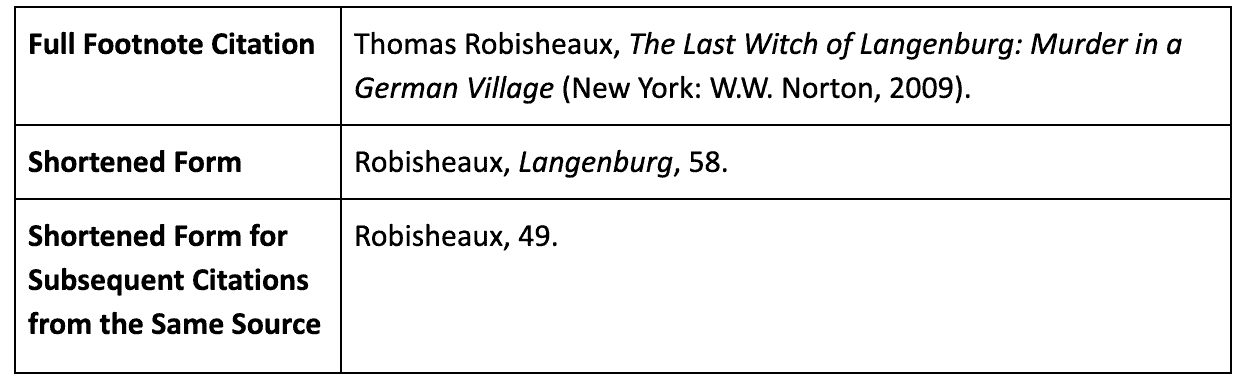

If you don’t plan to have a bibliography at the end of your work, make sure you use the full footnote citation form the first time you cite from a work. After the first citation, any other citations to the same work can then use a shortened form.

Updates to “Ibid”

It’s important to note that previous editions of the CMOS encouraged the use of “ibid” when the same source was cited multiple times in a row. “Ibid” is a Latin word meaning “in the same place.”

The 17th edition of the CMOS, however, overturns this recommendation because the use of “ibid” can be confusing for readers and authors can easily cite to the wrong source if they are not careful.

The current recommendation of the CMOS is to always use the shortened form of the citation. If you refer to the same work multiple times in a row, you may leave out the shortened title and just list the author’s last name and the page number to which you are citing (See CMOS 14.34 for more information.).

Full Bibliography

If you are including a full bibliography, you might choose only to use shortened citation forms in your footnotes or endnotes. You may also use the shortened structure that omits the title for sources that you cite several times in a row.

Keep in mind that if you cite a different source, you need to use the full shortened structure the next time you cite from a source you have used before. Here’s an example:

- Robisheaux, Langenburg, 58

- Robisheaux, 59.

- Robisheaux, 70.

- Cyrus, Scribes, 80.

- Robisheaux, Langenburg, 95.

Citation Examples

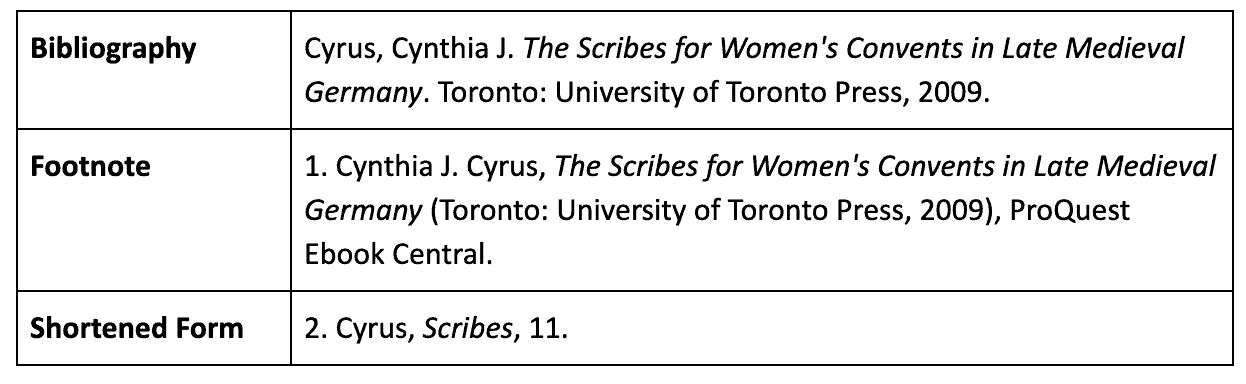

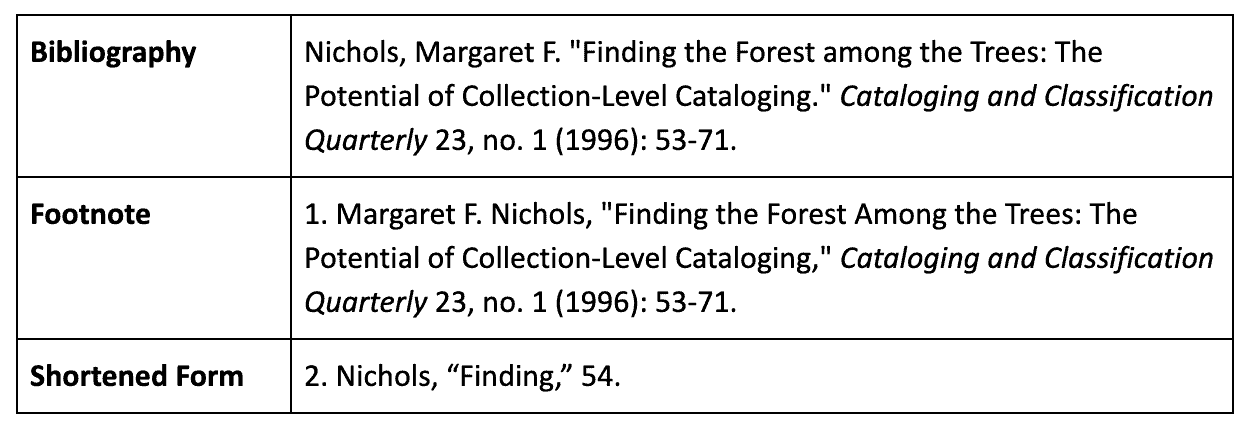

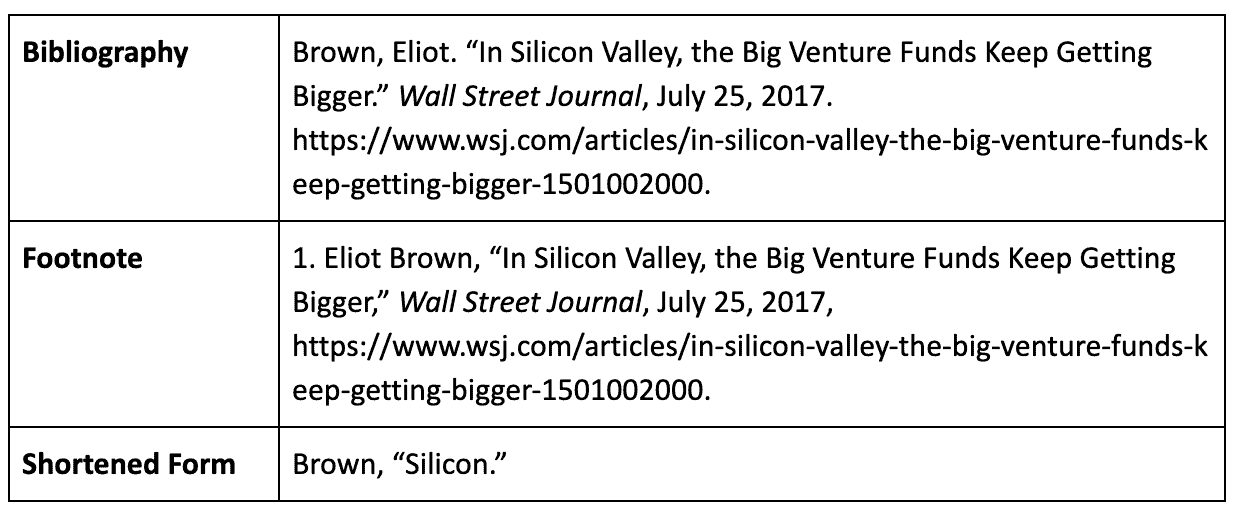

Here are a few examples of citation structures in the notes and bibliography style. For more examples and information on this style, check out the EasyBib Chicago footnotes guide.

Book:

Journal article:

Newspaper or magazine article:

Author-Date Style

This style uses parenthetical in-text citations and a reference list to guide readers to the sources you cite. The in-text citation generally includes the:

- Author’s last name

- Year of publication

- Page numbers referenced

Using the parenthetical citation, the reader can then look at the reference list and find full information for the source.The reference list for this style is usually titled “References” or “Works Cited” and is organized in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. The parenthetical in-text citation always comes at the end of a sentence, and is placed before the final punctuation.

In-text citation example

Nicholson’s study reveals a great deal about the general practices of ARL institutions in regard to the technical processing of these personal libraries. About half of the institutions kept the personal libraries shelved together and half used a Library of Congress classification scheme (Nicholson 2010, 114-115).

In the reference list, the citation would appear as follows:

Nicholson, Joseph R. 2010. “Making Personal Libraries More Public: A Study of the Technical Processing of Personal Libraries in ARL Institutions.” RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 11, no. 2 (Fall): 106-133.

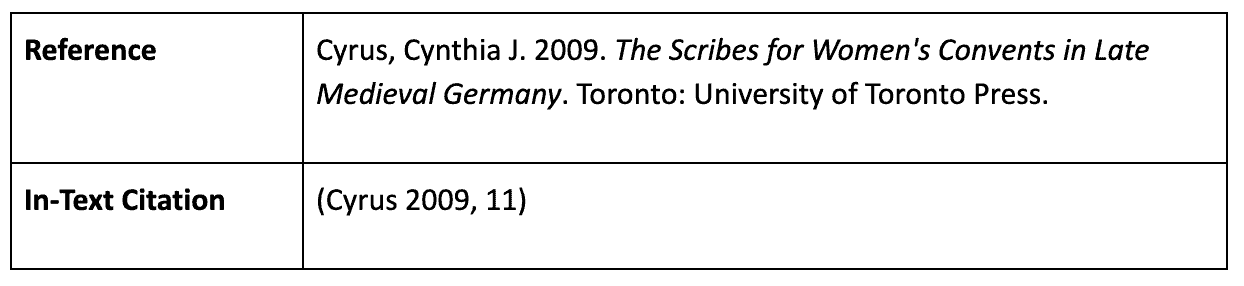

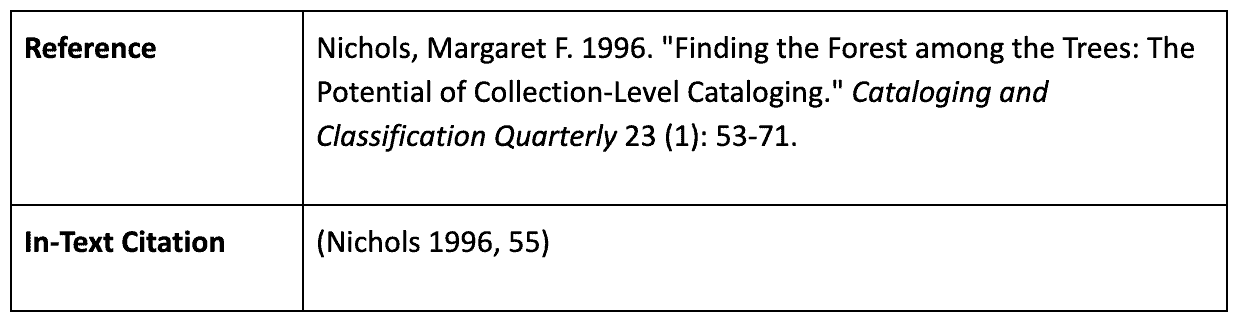

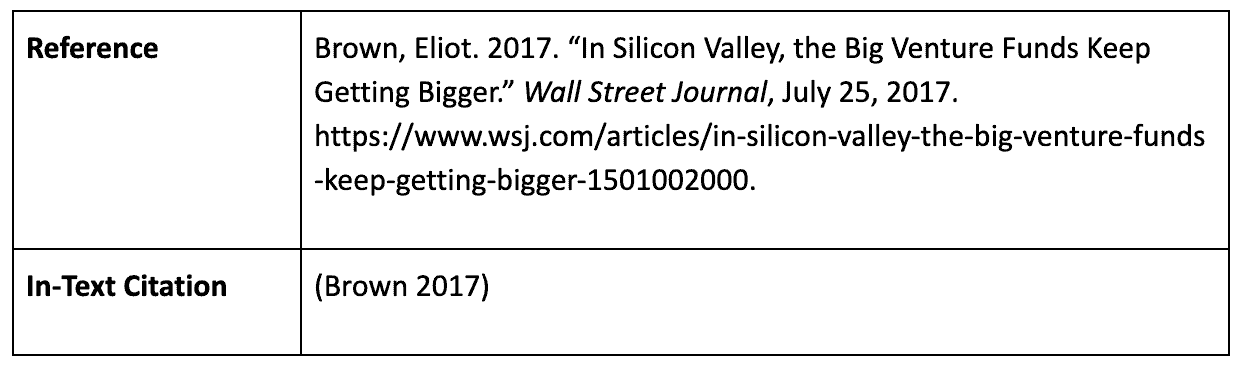

Additional Examples

Here are more examples of parenthetical in-text citations and their full citations as they would appear in the reference list. There are even more guides linked at the bottom of this page.

Book:

Journal article:

Newspaper or magazine article:

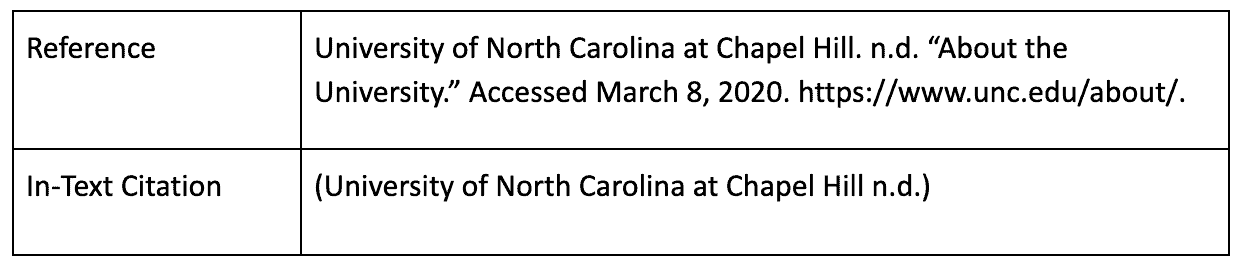

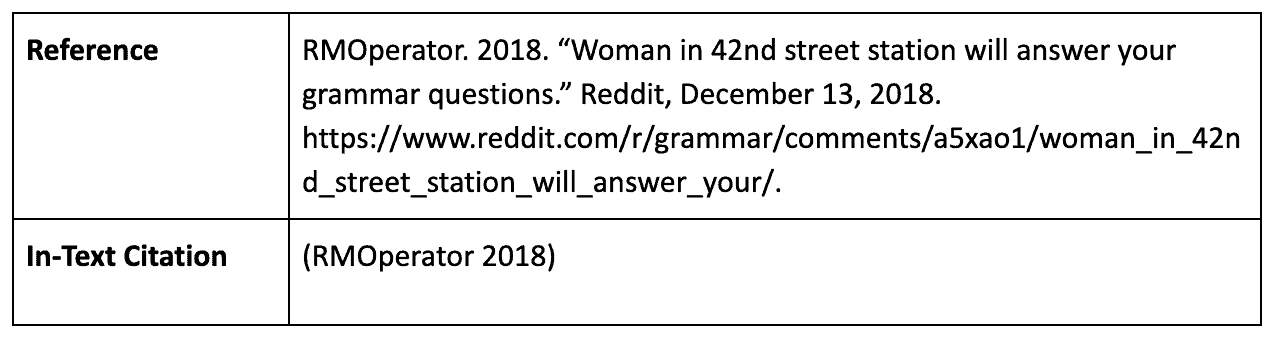

Website:

Social media:

In-text citation examples

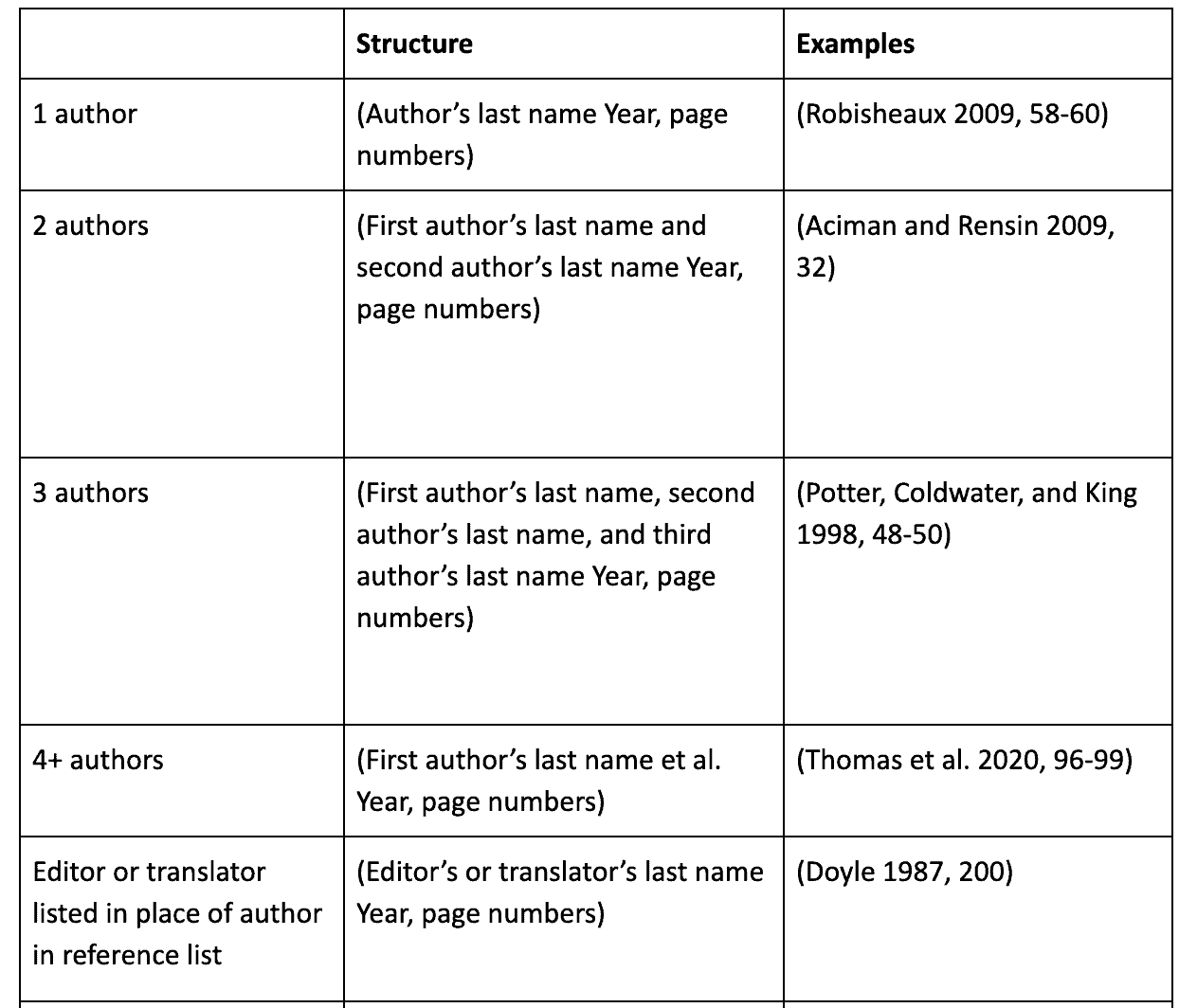

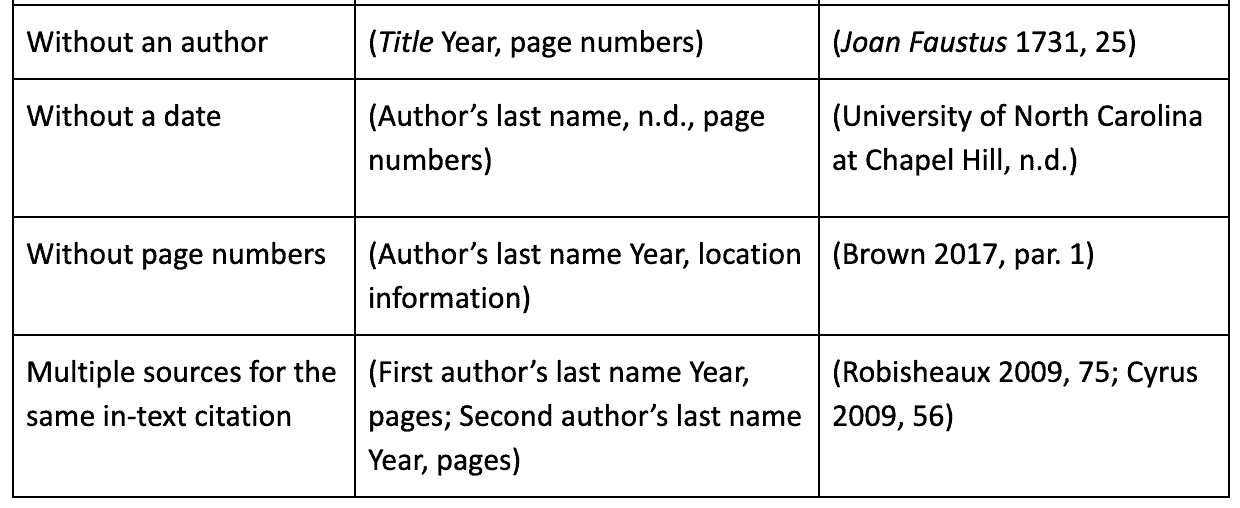

When building in-text citations, you might come across more complicated citations. This chart shows some of the most common citation types you will come across and how to build in-text citations for them.

Formatting Your Bibliography or Reference List

Bibliographies and reference lists are located at the end of your paper. You should include every source you cite in your bibliography or reference list.

Here are a few guidelines to follow:

- Center your title (either “Bibliography” or “Reference List”) at the top of the page.

- Organize entries alphabetically by the last name of the author (or title if no author is known).

- Each entry should be single-spaced with a blank line between entries.

- Each entry should also have a half-inch hanging indent.

3-em dashes

While sometimes 3-em dashes are used in bibliographies and reference lists in repeated list entries under the same author, the 17th edition of CMOS actually recommends that authors not do this in citation lists (CMOS 14.67 and 15.17).

Using 3-em dashes can cause a number of problems and it is best to just use the author’s name each time, especially if submitting your work for formal publication.

If your editor or publisher wants to use the 3-em dash, they will insert them where necessary. You can also check with your teacher and see what they want you to do.

For more guidelines for formatting bibliographies and reference lists, see CMOS 14 and 15 and Chapters 16 and 18 in the Turabian guide.

Other Chicago Guides

Citation Basics

Books

Periodicals

Online Content

Audio / Video / Photo / Art

- How to Cite a Film

- How to Cite a Musical Recording

- How to Cite a Painting

- How to Cite a Podcast

- How to Cite a Photo

- How to Cite Sheet Music

- How to Cite a TV/Radio Broadcast

Academic Sources

Other Source Types

Reference Materials

Bibliography:

The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.7208/cmos17.

Turabian, Kate L. A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations, 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Published October 31, 2011. Updated April 9, 2020.

Written by Janice Hansen. Janice has a doctorate in literature and a master’s degree in library science. She spends a lot of time with rare books and citations.